Those of us who live in Scotland have a decision to make.

We’ll make that decision for different reasons, having come from different starting points and with different assumptions – but decide we will, in what I expect to be startling numbers by comparison to recent democratic votes in the British Isles.

I have made my decision – and perhaps for the first time in my life, I’ve done so in a manner appropriate to the seriousness of that decision. It feels good.

If you’re turned off by referendum talk, click the back button now – because I’m about to explain why I’ve finally settled on a ‘Yes’ vote, then touch on some of my concerns for the future.

I started with ‘No’

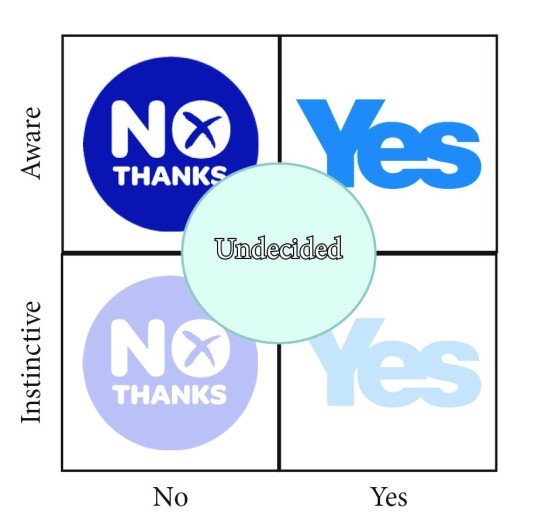

Having now been through 9 months of actively thinking about the question of Scottish Independence, I reckon the voting population is divided into some broad blocks:

My start position was one of Instinctive No.

What I mean by that is pretty simple: I would have voted No on the day the referendum was announced with little or no thought about my reasons for doing so.

There were a number of contributing factors to this basic position.

- I took for granted that the UK as it stands is a functional democratic system.

- I believed that change was possible within that system.

- I felt kinship with people throughout the British Isles, seeing the division between Scotland and the rest of the UK as largely arbitrary.

- I recognised that proposed change on this scale carried large risks which, in my gut, I didn’t think could be justified.

The Initial skirmishes

The core theme of my arguments at the start of this debate were, on reflection, about rejection of risk and division of community.

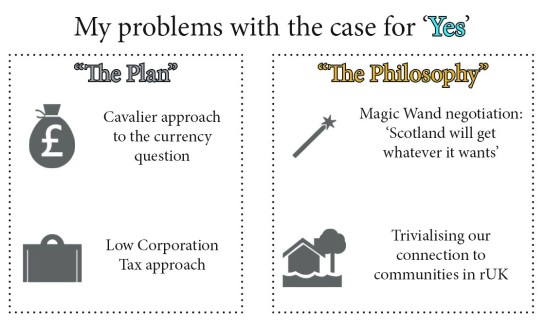

Elements of both the ‘Yes’ campaign’s plan and their apparent philosophy sat uncomfortably with me:

The economic questions were vexing.

- Why would I vote for independence, when the Scottish Government appeared to be more interested in brinkmanship over currency union than ensuring that a workable option would be available?

- How could I back the Scottish Government’s plan to slash corporation tax, when I could foresee it creating a Scotland in which powerful corporations were handed even more influence than they currently enjoyed?

Equally troubling were the attitudes apparently displayed by ‘Yes’.

- It would appear that I all I had to do was think of a positive impact or institution associated with the union, and ‘Yes’ would instantly tell me I could keep it. This flies in the face of everything I have learned about negotiation, making the ‘Yes’ campaign sound extremely naive.

- To argue that Scotland is home to a natural, left-leaning consensus which makes it a better independent country sat awkwardly with me; as a person of the left, I instinctively identified more with other left-leaning communities in the UK than I did with the general population in Scotland. Leaving those communities behind in favour of our ‘nation’ did not seem a positive step.

In the early days of my personal debate, the words of the ‘Yes’ camp and its supporters offered cold comfort on these issues. I was not impressed.

A surprising demographic

One of the first phenomena which really struck me, as the debate opened up, was the sheer volume of people in my social circles who identified confidently with ‘Yes’.

As an instinctive ‘No’, I had unconsciously assumed that my peers would have similar feelings about the referendum – a position which, in hindsight, seems bananas. Nonetheless, that default idea produced a jarring collision when it met reality: in fact, numerous friends and family members, people whose intelligence and politics I had great admiration for, were committed to voting for independence.

Humans are terribly self-deceiving creatures. We like to believe that we’re very rational, but a great deal of our decision making is actually driven by our emotions. Seeing people close to me, ready to support an idea I had all-but-dismissed, was the first significant signal that I might have more to consider than I initially thought.

The Chancellor came to town

One day, George Osborne stood up in Edinburgh and told everyone involved in the debate that a formal currency union between iScotland and rUK would not be considered by any of the Westminster parties.

It all seemed a fairly predictable negotiating position.

I wasn’t taken aback by this; in fact, at the time I welcomed the injection of some realism into the currency debate. It irked me that Alex Salmond seemed to be ignoring the realities of negotiation, ie. that the party with the most power will wield it to obtain the best result; he was presenting to the Scottish people the idea that their country would depart the UK in peace following some friendly discussions, which was (to my mind) clearly bollocks.

Shortly after this piece of political theatre – and amid the rising din of Scots voices which took exception to being ‘bullied’ – I had a discussion with my brother about the shape of the debate. A ‘Yes’ supporter, he passionately criticised the unwillingness of the UK government to pre-agree the terms of what an independence settlement would look like.

“They owe it to the people of Scotland to let us know what options we’re actually voting on,” he asserted.

I scoffed at this notion. I asked him why on earth Westminster politicians would do such a thing, when it was manifestly not in their interest? I reminded him that no-one had the power to compel the UK Government to do such a thing – and that ultimately, power was all that mattered in this equation.

My brother was disgusted, but I felt I had won the point.

I didn’t realise how my own words would continue to echo in my ears: this stunt was about British power, a theme which would recur uncomfortably in future discussions.

What does Britain stand for?

I had some indistinct ideas about what the UK was, coupled with an even more indistinct understanding of its imperial history, prior to the beginning of this debate. They were based on teen years partly immersed in a popular sense of Cool Britannia, on a love of institutions such as the BBC and the NHS, even on the sense of community and shared triumph which emerged from the 2012 London Olympics.

On reflection, it became obvious that I knew very little about what Britain really stood for.

These murky notions did not stand up to contact with informed conversation.

I understood that Britain had been an imperial power, that its rule in certain high-profile places (like Ireland) had been contested and had even precipitated violent struggle. But what I didn’t understand, as a child of the 1980’s, was just how large the Empire had been – and how blood-soaked had been its exploitation of the world’s peoples.

I don’t intend for this article to run to 500,000 words, so I won’t attempt to list every morally repugnant action of the Empire. What I will say is that Google exists, and there are plenty of resources out there which will help to fill you in.

With a new understanding of what the British Empire had been built upon – namely, a desire on the part of the crown and mercantile elites to vastly enrich themselves – I found some of my basic, unconscious assumptions about Britain’s validity challenged. This in turn led me to examine the workings of the contemporary UK with a more critical eye. What did Modern Britain stand for?

Since a particularly progressive post-war period, it’s clear to see the history of the UK taking a turn toward unpleasantness, beginning with the time of Margaret Thatcher. We’ve been invited to lionise those who seek to acquire vast wealth, on the basis that once they are successful, they’ll need ‘little people’ to do things for them and their wealth will ‘trickle down’ into the pockets of everyone else.

Over successive years, any ‘trickle-down’ tends to dry up as wealth consolidates.

In reality, of course, Capital has tended to appreciate at a rate higher than that of wage inflation – put simply, the rich have gotten on with the job of getting richer, while the vast majority of the population have lagged further and further behind in their earnings.

Thomas Piketty has more and better to say on this subject than I do, but my point is basic: a modern nation practically designed to facilitate greater concentration of wealth simply can’t be acting in the interests of most of its citizens.

I don’t like the fact that this is an ever-present philosophy in today’s UK – but I can vote to change it, right?

The incumbent or the System?

One of the oft-repeated jousts of this campaign has been around which choice the people of Scotland are actually making.

The SNP have presented it as a chance to ‘get rid of the Tories forever’; the Better Together campaign has pointed out that we have elections to dispense with governments we don’t want – and that constitutional change is a larger thing which they don’t believe is warranted.

I make no bones about the fact that I don’t like the current incumbents in Westminster; however, I instinctively agreed that elections were the appropriate mechanism by which to change the way we are governed. That’s until one of my discussions reminded me of the last referendum we were invited to take part in.

Voting mechanism

Hey, remember AV?

It maybe hard to believe, but as recently as 3 years ago, we had a chance to change the way voting was conducted in the UK. Sadly, the campaign to promote that change was tepid and ineffective – while the campaign to prevent it was well-funded and aggressive. In the end, the AV referendum changed nothing and perhaps even entrenched traditional voting structures.

AV wasn’t a perfect option – I’d prefer full proportional representation, personally – but it did represent progress in the right direction. The existing UK system, first-past-the-post (FPTP), works to ensure that only established parties with critical mass can win large numbers of seats and take power.

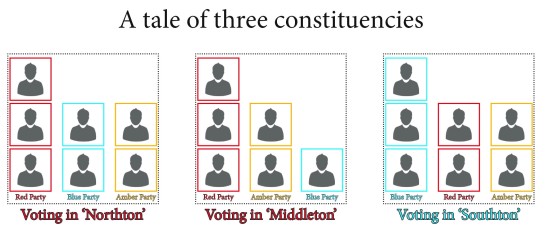

Let’s briefly recap FPTP by studying the fictional country of Postland, which has three constituencies and uses the FPTP system to elect its governments:

This year, the Red Party have swept to power with a one-seat majority over the Blue Party. The Amber Party are unrepresented in parliament, having failed to come first in any of the constituencies.

Wait a minute, though – it seems that when we look at ballots in Postland as a whole, both the Blue Party and the Amber Party received 6 votes. That means that simply by virtue of the way the boundaries are drawn, grouping more of the Blue Party’s supporters into Southton, they are handed a voice in the affairs of the nation while the Amber Party’s supporters are shut out completely.

Now, don’t get me wrong: with a three-constituency map, that guarantees nothing but invincible majorities or completely hung parliaments, Postland has a whole range of problems. Nonetheless, it elegantly illustrates how a FPTP system can close the door on parties which don’t have sufficient geographic concentration – or, if we’re being cynical, haven’t held power recently enough to gerrymander constituencies in their favour.

When parties can’t win seat totals reflective of their actual electoral share, it makes it harder for them to be taken seriously by undecided voters, which in turn limits their ability to attract or retain votes. This compounds the situation which over-rewards parties with a critical mass of traditional supporters.

What does that mean in the UK?

Well, the BBC have already put together an excellent resource on the political battleground they expect for the 2015 General Election. Have a look here.

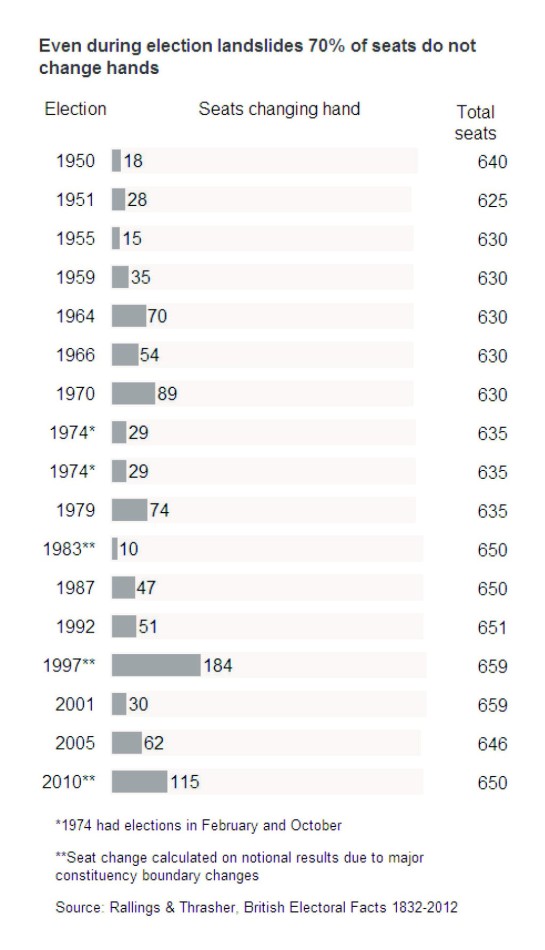

There’s a lot of information to absorb on the site I’ve linked, but one key statistic is prominently highlighted:

Sourced from the BBC’s excellent Election 2015 resource, at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-25949029

This tells me something, loudly and clearly:

- In 2010, only 2 in every 11 constituencies actually mattered.

- …and within those constituencies, only the narrow percentage of swing voters actually mattered.

I don’t live in a ‘marginal’ constituency so, in Westminster elections, this means I effectively don’t have a vote.

In the past, I’ve thought about the implications of this set-up, become frustrated and moved on to think about something else. However, in the context of a vote on constitutional matters, it takes on a renewed importance: for the first time, I actually have a meaningful lever by which I can force things to change.

Converging Party lines

Let’s put that thorny issue to one side for the moment. If we imagine that our votes do make a material difference to the outcome of General Elections, can we use those votes to elect a party which will challenge the dominant, neo-liberal, free-market ideology?

Well no, not really.

Traditionally, voters with my personal sympathies would look to the Labour party for a viable alternative; today, I find a party which has accepted the ‘Austerity’ narrative completely, choosing to tout slower cuts as their significant point of difference.

Labour’s response to the privatisation of Royal Mail is to criticise the price at which the current government chose to float the business, rather than to ask: “How can turning over a crucial public service to an outside organisation, which will prioritise extracting a profit margin, possibly lead to a better experience for the people of the UK?”

Perhaps most damning of all, Labour’s Ed Miliband gave an interview to Krishnan Guru-Murthy of Channel 4 News earlier this year, in which he appeared to express sympathy for UKIP-esque ‘worries’ over immigration. To my mind, it was a lurch in response to a surge in support for UKIP – and the opposite of what I want to see a party of the left saying to the public. If you play up to the idea that, ‘…they come here, taking our jobs…’ you do not speak for me.

I have no faith in the Labour party to deliver a reversal of the political tide in the UK – and that’s a big issue indeed.

The illusion of ‘Status Quo’

Taken as a whole, these factors add up to an almighty problem (in my opinion) with the current constitutional settlement in the UK… but there’s more.

You see, it isn’t the case that the current situation is a static one. We can’t defer action until successive elections have passed, expecting problems to stand still until we can build a consensus to change them – the UK is moving all the time down the road of whatever dominant political consensus holds sway.

I’m not happy with our direction of travel, and standing still is not an option.

Re-examining my basic assumptions

Early in this article, I outlined some key ideas about the UK which underpinned my instinctive position:

- I took for granted that the UK as it stands is a functional democratic system.

- I believed that change was possible within that system.

- I felt kinship with people throughout the British Isles, seeing the division between Scotland and the rest of the UK as largely arbitrary.

- I recognised that proposed change on this scale carried large risks which, in my gut, I didn’t think could be justified.

By July of 2014, the first two of these assumptions had been demolished by reading, contemplation and debate – and with them, all certainty about my voting intentions.

My third assumption, about how I identify on social and political lines rather than on a national basis, was going nowhere (and still hasn’t). I just don’t have a nationalist sentiment worth speaking of.

That left me with one particularly big issue to address: risk.

Striking a realistic balance between risk and reward is difficult – particularly if one’s nature is to be risk-averse.

My key concerns

I am a naturally risk-averse person, but I do at least understand that humans take risks every day – and that there is no way to truly ‘play it safe’ in life.

I decided to write down my most important concerns about Scottish Independence, then attempt to weigh the risks and rewards associated with them in the most sensible way I could.

The Economy

I felt that the position of the SNP, arguing that currency union was the only sensible way forward and that the rUK would quickly reverse its position in the event of a Yes vote, was idiotic. The main parties were united in their opposition: the opinion of the rUK would only harden if Scotland decided upon independence.

During the debate, when this confidence problem with voters became apparent, the SNP tried to move the goalposts by claiming that ‘no-one could stop us using the pound’ – a reference to so-called Sterlingisation, wherein Scotland would use the Pound as Panama does the US Dollar – as if that was somehow a position comparable to what they had been arguing for.

I’m not an Economist, but I can confidently say it’s not. Adopting a foreign state’s currency as our own would put Scotland in a radically different position than that of true monetary union, with reduced powers of borrowing and a necessarily careful approach to managing debt and risk. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it sure as hell isn’t the same as what Salmond et al had been advertising. To say otherwise was disingenuous and inspired zero confidence.

Not having a plan to issue our own currency in the event of currency union being unobtainable was a stupid mistake. I haven’t changed my mind about that.

With that out of the way, however, my exploration of Scotland’s economic prospects left me more optimistic about our fortunes than I had initially been.

Much has been made of the Financial Times’ analysis that iScotland could ‘…expect to start with healthier state finances than the rest of the UK,’ but with good reason. Ratings agencies have delivered similar endorsements. There is serious economic strength and potential in this country – but it’s not all about money.

Unpleasant division

The Scotsman, in a brilliant editorial on 20 August, gave voice to one of my gravest concerns:

The Scotsman nailed it: this debate has inevitably awakened an emotional reaction amongst those in the rUK. Whatever happens, we must be prepared to deal with that.

The paper highlighted how the prospect of a Scottish departure from the union – and the rhetoric which accompanied it on both sides, with pro-independence campaigners frequently painting Scotland as ‘subsidising the UK’ and unionists suggesting the opposite – was generating ill-feeling and resentment amongst those south of the border.

This seemed an eminently sensible observation, yet one which the ‘Yes’ campaign tended to blithely ignore. Wrapped up in that bullish assertion about the rUK ‘coming around’ to currency union were a host of other assumptions about how nicely everyone would behave whilst facilitating a Scottish exit from Britain. It’s claptrap. They won’t.

If you need to take a cue from anywhere about how alienating the Scottish debate might be for our close neighbours, look no further than the way we have alienated each other over the course of the referendum campaign. Social media is awash with public flame wars, or worse, tribal groups in which campaigners of like mind can speak to each other in endless echo-chamber environments, hearing only ideas they agree with and reinforcing their zealotry.

Let me tell you: as an undecided voter, nothing is more off-putting than zealotry.

Ultimately, it was pragmatism that reconciled me to this risk. As the Scotsman so clearly points out, this rise in ill-feeling is ‘in the mail’ – if they (and I) are right, it’s coming now, no matter the result. There is no point in fretting, only in planning the best way to repair relations.

On a related note, I am not minded to worry about exercise of British Power against an independent Scotland. Since that strange day when I ‘won’ an argument with my brother by pointing out that anti-democratic brute force was the first (and logical) resort of the UK, I have been waking up in stages to the fact that I hate living in a country where such a thing is true. I would prefer to treat with a smaller government, less well-equipped to steamroll the wishes of its citizens.

Taking the chances you have vs. Wishing for better ones

Football is a beloved passion in this part of the world, both North and South of the border, so it’s fitting that a football analogy should slot so neatly into my referendum thinking.

In analysis of the beautiful game, much is made of a player or team’s ability to ‘take their chances’. The most effective footballing units are those which capitalise on the opportunities that materialise; some of those chances will be slim, difficult to convert, while others will feature open goals.

Here’s the thing: as a person who wants constitutional change in his country, a change of mindset in his leaders, can I really afford to overlook the chance which this referendum offers?

It may be emotionally comforting to bemoan the fact that our chances aren’t easy to take – but it’s ultimately fruitless.

It’s not a perfect chance. The SNP are in power, a party I don’t like, with suspicious pro-corporate leanings of their own; there are uncertainties about how the economic picture will play out, too. We might consider this an opportunity at the Goalkeeper’s near post, on the volley – one which requires a hard sprint to ‘get on the end of’ and difficult technique to finish, as it drops out of the air.

However, if we decide not even to attempt the sprint, are we guaranteed another chance? Dare we hope for an open goal to materialise in the closing minutes, so we can have things just as we want without much effort?

Anyone who follows football will know the answer to this question. There are no more guarantees in the independence game than on the pitch, but if we don’t trust ourselves to get a shot on target, to overcome the problems then we are already caught in the grip of a losing mentality.

In any case, even if the open goal does show up, it’s still possible to balloon a shot over the bar – just ask the Lib Dems, who went into their coalition negotiations confident of securing the Alternative Vote.

The last hurdle

It was only in the last 12 days or so that I finally made my peace with the final, gigantic obstacle positioned between me and a ‘Yes’ vote: my disdain for the online behaviour displayed by a huge, visible constituency of ‘Yes’ campaigners.

I accept that this will not be a popular segment of my commentary, but so be it. Over the 10 months in which I’ve been fully engaged with this issue, I’ve seen a number of behaviours which utterly turned me off from voting ‘Yes’:

- Shouting down of reasonable doubts, questions and arguments for a ‘No’ vote (including ‘pile-on’ takedowns where more and more posters join in to pillory an individual).

- Personalised attacks, shameless ad hominen, straight-up name-calling.

- Sneering dismissal of individuals’ right to hold a contrary opinion.

I’ve heard a host of denials about this phenomena, but they don’t cut it. Unless my experience is a statistical fluke, the online ‘Yes’ community is awash with attack politics – and that modus operandi has surely chased away a host of potential voters.

I’m thankful that I’ve found at least one oasis of sanity online, in which I could discuss issues reasonably (if passionately) with people from both sides of the debate; others may not have been so lucky.

It took a long, honest conversation with myself to realise that I was ready on almost every front to vote for independence… but I was holding back, not ready to be associated publicly with the bluster, pomposity and ‘monstering’ which I had seen perpetrated by supporters of the ‘Yes’ camp.

Once I realised the truth, it was time to bite down and push through it. There may have been a handful of scenarios in human history where failing to do what was right because of perceived social stigma was helpful, but I really can’t call one to mind.

Of course, it was helpful that the Better Together campaign chose my long, dark tea-time of the soul as the moment to release their ‘Patronising BT Lady’ advert.

The booming voice

Several weeks prior to my first viewing of the advert, I was engaged in conversation with a pro-independence friend of mine about the phenomena I describe above.

The discussion had many twists and turns, but we reached a pivotal point when I was describing the volume of nasty ‘Yes’ commentary which I observed online, with very little visible counterbalance.

“Perhaps they feel the need to shout and make waves because what they are struggling against is so ever-present and oppressive,” he suggested to me. “You aren’t hearing it, perhaps because it’s been all around you for so long, but trust me: when you really listen, the voice of the Establishment booms.”

I heard and noted his words at the time, but they didn’t become real to me until I watched The woman who made up her mind.

The most wretched political advert ever devised.

The film is a little under 3 minutes, but the producers have crammed a lot in. There is lazy sexism; there is an implication that the people (and specifically women) of Scotland are so disengaged with politics that they are ignorant even of the First Minister’s name; there is a smug, dismissive invitation to ‘forget thinking about the referendum’ and just ‘vote the right way’.

I watched, and heard it for the first time: that smooth, patronising, booming voice. I could hear the Establishment talking… and it was talking down to me, to everyone around me. It was telling me not to be so silly, to get back into my box.

I felt disbelief, then fury – then amusement. This was perhaps the most ill-judged political advert of all time and, in my case, it had spectacularly backfired.

I was going to vote ‘Yes’.

Living together on 19 September

In the context of this referendum, there are two certainties:

- A large number of people in Scotland will not get the result they wanted.

- We will all still have to live together the morning afterward.

I have the profound sense that regardless of the vote’s outcome, the biggest and most important job for the people of Scotland will be conciliation.

While this campaign may have seemed interminably long, it’s nothing compared to the length of time that Scotland will live with the outcome of the vote. We can’t, we mustn’t, allow some of the embittered tribalism which has surfaced in the debate to poison whatever our future has in store for us.

Things I won’t be doing

I’m not going to do anything to encourage that tribalism.

- I will not be adding a ‘Yes’ button to my Facebook profile picture, or my Twitter avatar.

- I will not be chiming in on the pages of all my friends and acquaintances to tell them how they should be voting.

- I will not be dismissing those who have different voting intentions than I do as ‘stupid’, nor will I allow others to do so unchallenged.

- I will not consciously contribute to ‘echo-chamber’ online politics, which slowly conditions participants to become carelessly strident and insensitive to other points of view.

- I will not pretend, in debate, that everything will be easy if Scotland votes to be independent – because to do so is patently daft.

Things I will be doing

- I will encourage others, if and when the conversation comes up, to make sure they vote.

- I will suggest taking the time to read and think about the decision – and to genuinely consider that other points of view might have more value than our instinctive positions. None of us are too busy to have a think.

- I will answer honestly if I am asked about my voting intentions, and about my belief that although establishing a new country will be tough, it will be worthwhile.

- I will, in the event of a ‘No’ vote, not sulk or lash out vengefully at my fellow Scots; instead, I’ll keep trying, through my words and actions, to make our community the best home it can be for all of us.

The round-up

I’m a communicator by trade; this post has broken all my own rules about keeping things short and to-the-point. I’m fine with that in this case – once in a while, it’s OK to go into detail about important things.

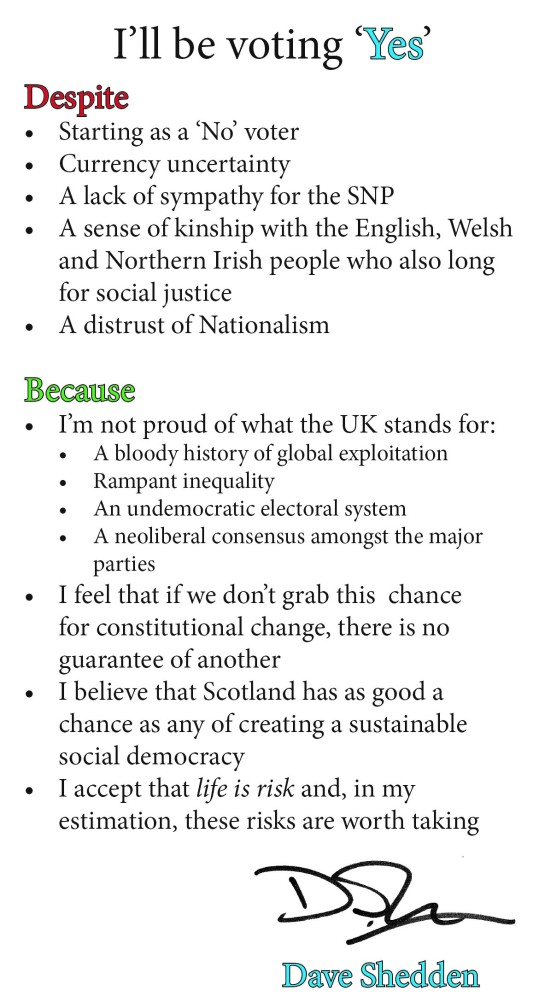

As a nod to my basic sensibilities, however, I’ve produced a cheat-sheet for this article, which you can see below.

I don’t have a fail-safe plan for creating the society I want – but truthfully, no-one does. My initial mistake was assuming that the current system offered a good opportunity to create that society, without considering the alternatives.

So there we have it

How you’ll vote in this election is your business, and I’m not going to try and browbeat you into agreeing with me.

What I will ask you is this:

- Take some time.

- Challenge your own assumptions, whatever they may be.

- Reach a decision for reasons you understand, and can stand behind.

- Be ready, win or lose, to make peace with your neighbours and build the best life you can, starting on 19 September.

That’s as much as any of us can do.

Dave